Being Seen: Power Through Diversity Gallery Guide

September 20, 2020 in conjunction with Arkansas Peace Week, September 20 – 27, 2020

This guide offers insight into artwork that is part of the Being Seen: Power Through Diversity online exhibition.

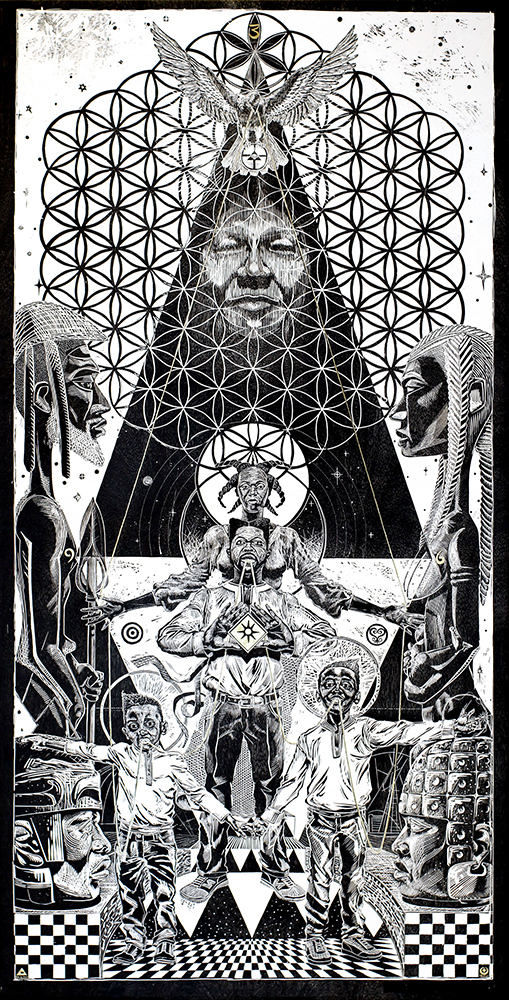

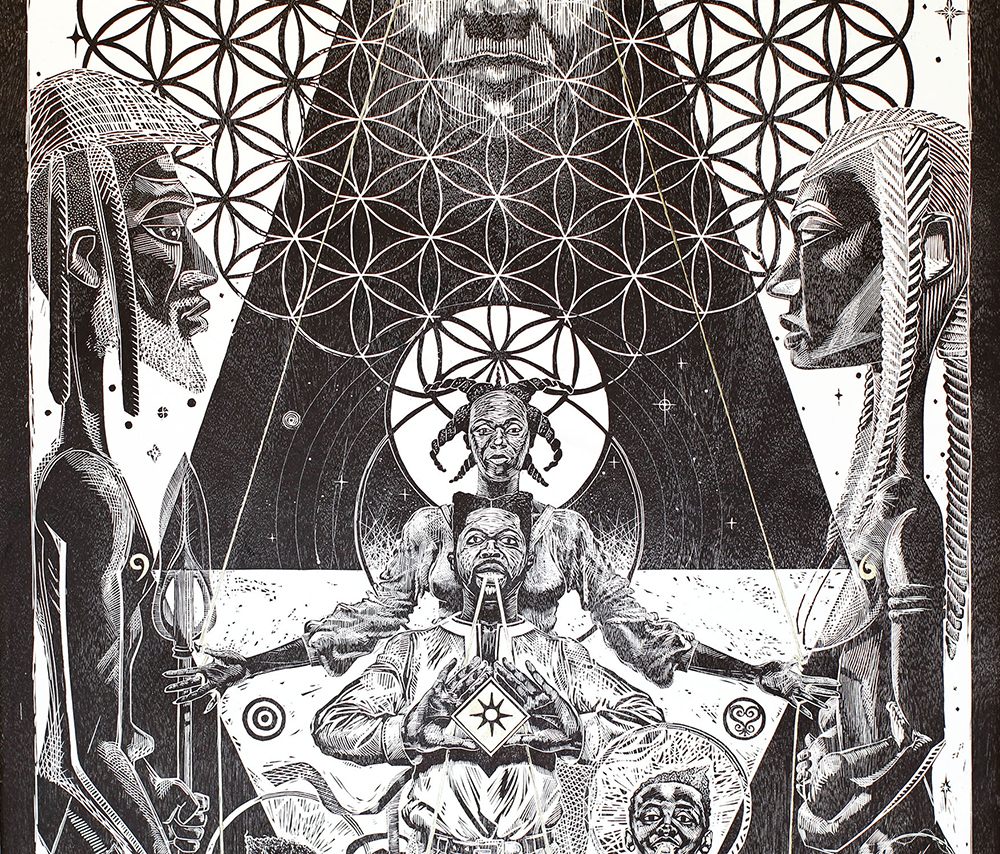

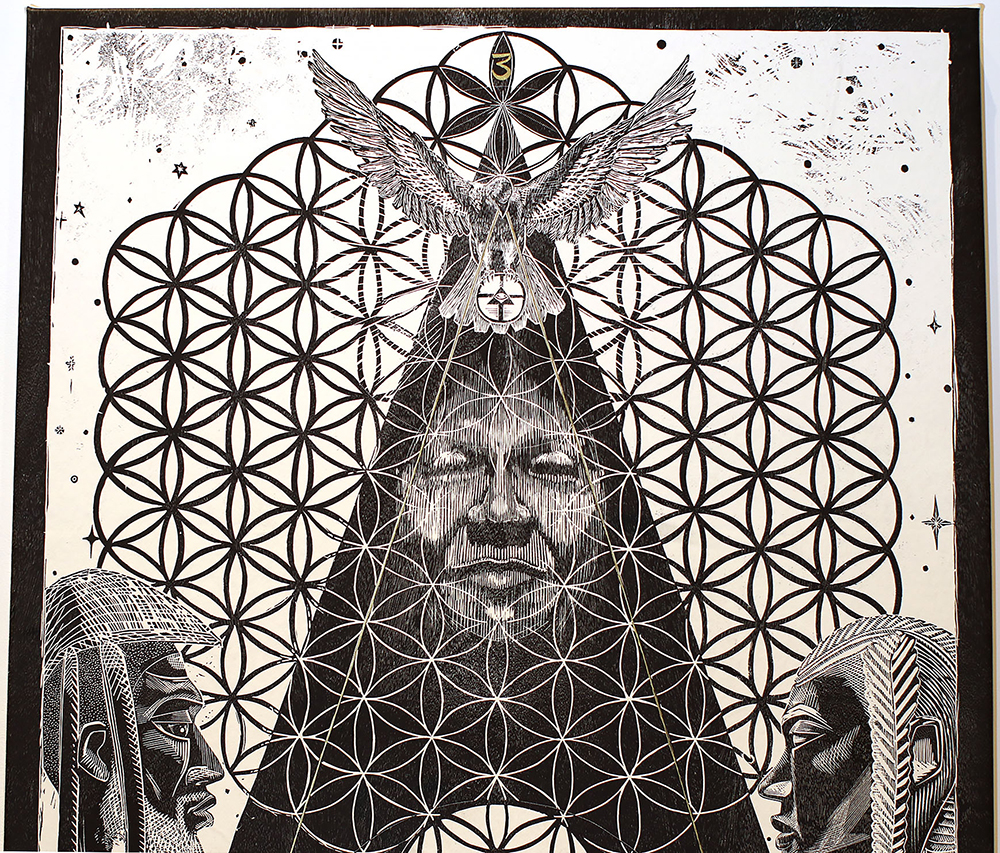

Ariston Jacks

American (Pine Bluff, Arkansas, 1973 -)

LOST GATE – (Lineage of Supreme Triumph) (Generational Ascension Through Excellence) (2019)

76” X 39”

Edition: 4/5

oil based relief ink, Japanese paper, from carved mahogany wood panel

Printer/Publisher: Big INK (New Hampshire)

UA Little Rock PC 2020.002

This six-foot woodcut is a story within a story about family. This is a family of artists in an unnatural environment where they receive blessings in the form of inspired visual imagery from their ancestors. Within this allegorical family portrait there are references to super natural phenomena, metaphysical data, ancestry, and the mystery of American truth.

The artist’s (Ariston Jacks) Elders lead the family to the gate of consciousness; as a result the family shines through the atmosphere reconfiguring time & space as they move forward in thankfulness. In time their children will do the same as they all continue to ascend up to heaven through the narratives passed along from one generation to the next.

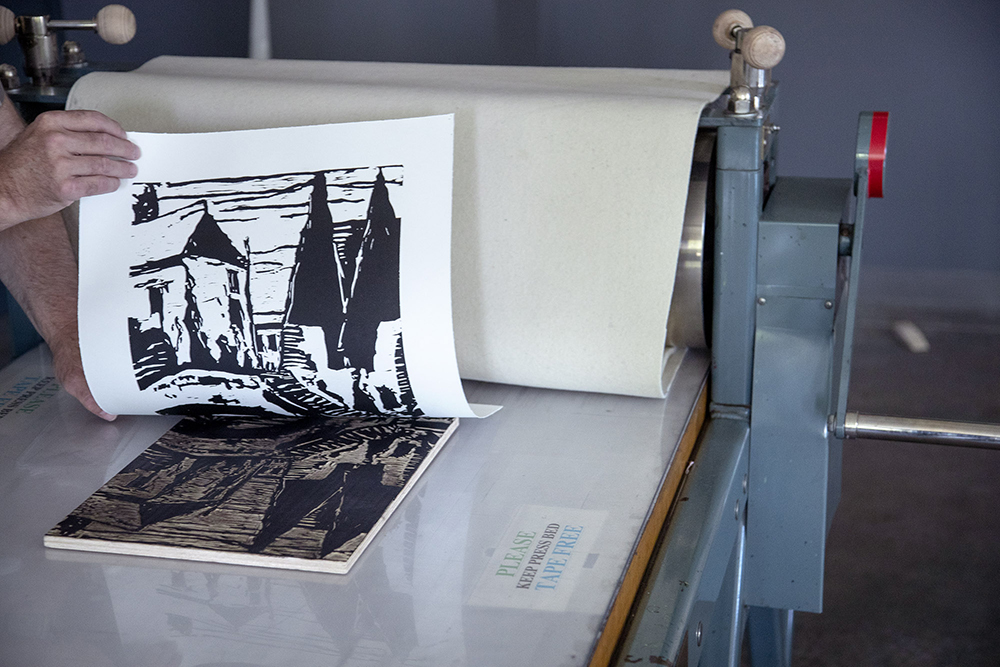

Relief Woodcut Printing

Relief woodcut printing transfers ink to paper in a process similar to rubber-stamping.

An artist transfers a drawing to a block of wood. Some shapes in the drawing will be cut away. These areas will not hold ink. The raised shapes that remain will hold ink. Inks are applied to the wood plate with hand rollers. A press transfers the ink onto paper. The final print is a reverse impression of the image cut into the plate. Multiples impressions can be printed. The plate is inked up each time. Each print in the edition is numbered (i.e., 4/5) and signed by the artist.

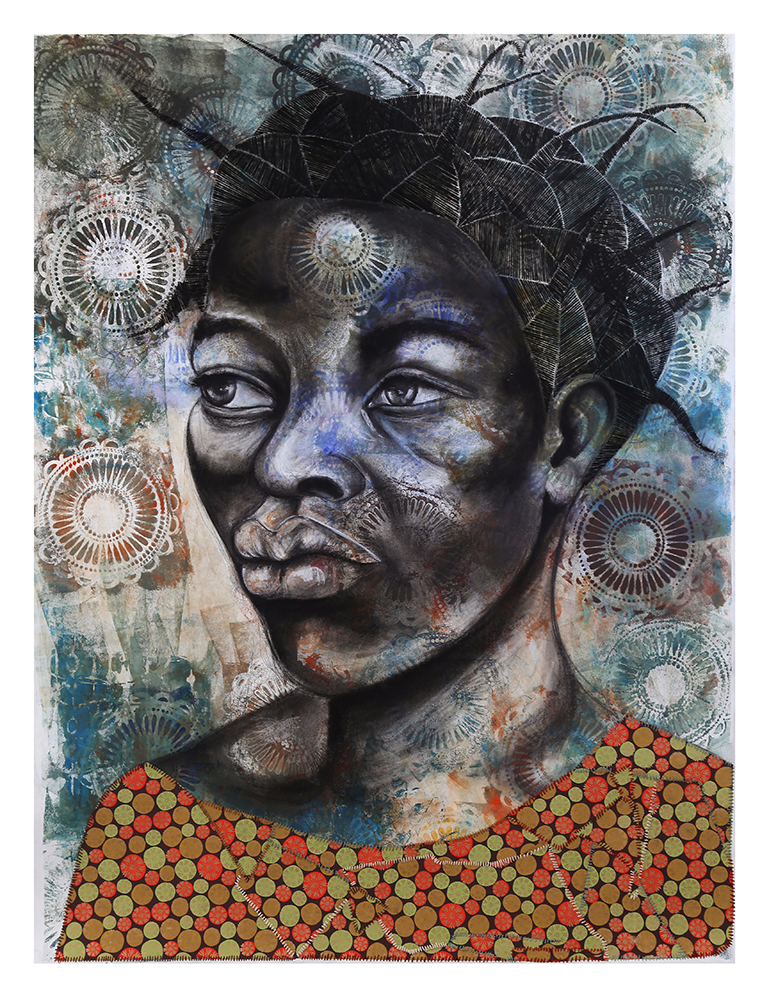

Delita Martin

American (Conroe, Texas, 1972 -)

Standing in the Night (2013)

69″ x 52 1/8″

Mixed media on paper

Image Courtesy of the Artist

UA Little Rock PC 2014.015

Delita Martin incorporates various printmaking techniques, drawing, collage, and woven thread into her large-scale portraits. This portrait was included in the exhibition “I Come From Women Who Could Fly: New Work from Delita Martin” (2014) presented by the Arts & Science Center for Southeast Arkansas. It was also selected to be in “State of the Arts: Discovering American Art Now” (2014) at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

Martin’s work has been exhibited both nationally and internationally. Her first solo museum exhibition was “Delita Martin: Calling Down the Spirits” (2020) held at the National Museum of Women in the Arts.

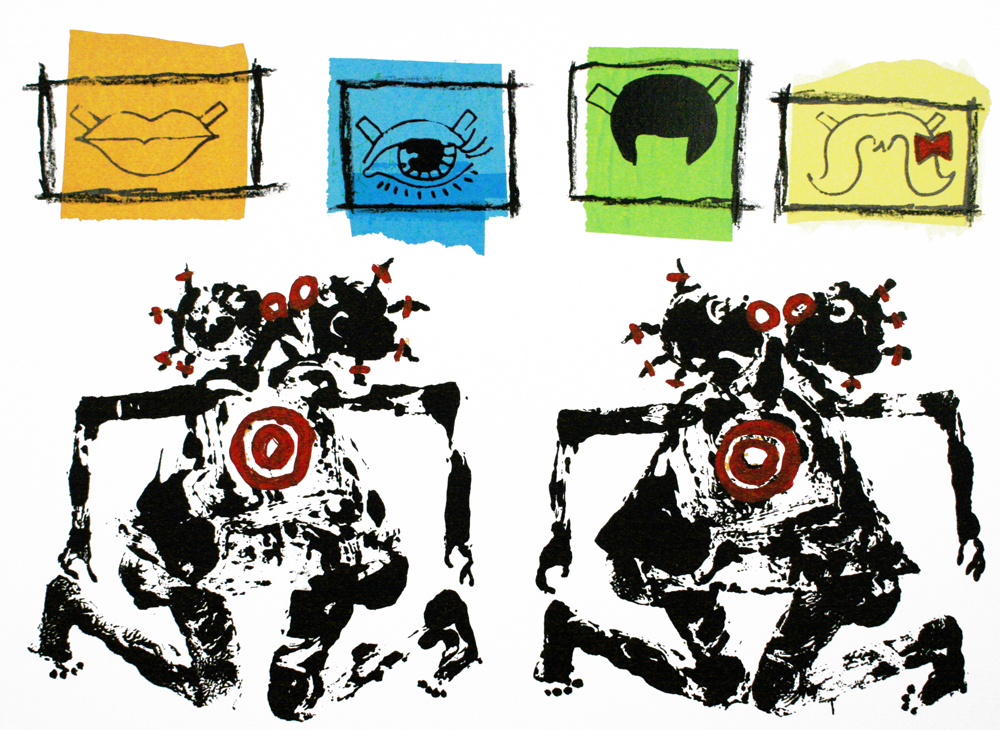

Deborah Roberts

American (Austin, Texas 1962-)

False Impressions (Serie Project XIII) (2006)

14 ½” x 21”

screenprint

Edition: 44/50

Printer/Publisher: Coronado Studios, Austin, Texas UA Little

UA Little Rock PC 2011.004.207

Change, they say, is life’s only certainty. For Deborah Roberts, this maxim has held true throughout her career as an artist. Roberts is formerly known for her narrative works depicting Norman Rockwell-inspired, African American community portraits.

In recent years, however, Roberts’ work has undergone a change for the contemporary, which has catapulted the Austin-native to new heights of success internationally.

For Serie XIII, Roberts created False Impressions, a print showing dual figures of two women holding each other in a circumscribed circle. Roberts describes one of these figures as an ancestral link to the second figure representing a culturally manufactured response to the past.

Above the figures are four boxed images representing the different masks used to define beauty in American culture. Roberts explains that the boxed images are symbols of assimilation that black women have used to be perceived differently, false impressions about women of color that Roberts considers indefensible:

“Our [African American] identity is tied up in how we are perceived and in misconceptions that have imprisoned our growth.”

False Impressions is meant to challenge images of black women propagated by mainstream media and by centuries of racism because as the artist states: “if we choose to change the way in which we are viewed, then we change who we are as people.”

Screenprint / Silkscreen (Serigraphy)

Silkscreen (or serigraphy) is a printing process that uses a woven mesh (traditionally silk) to support a stencil printing technique. Open areas of the mesh act as the stencil, which allows ink to transfer onto various materials (i.e. paper, plastic, fabric and metal). Ink is pressed through the mesh of a silkscreen with a fill blade or squeegee. When the squeegee is moved across the screen stencil, it forces the ink through the openings of the mesh onto paper, plastic, fabric, or metal.

Joe Jones

American (1909 – 1963)

The Struggle in the South (1935)

dimensions variable

Commonwealth College Mural, Mena, Arkansas

tempera on Masonite

Located at UA Little Rock Downtown Campus

Saving The Commonwealth College Mural,

The Struggle in the South, by Joe Jones

The colors were faded and the paint chipped. Pieces of the mural were riddled with nail holes, scratched, damaged by water and age, but the powerful stories shone through. The history, the struggle, and the perseverance of the characters painted on the panels were as strong as ever.

So begins the challenge to save the 1935 mural, The Struggle in the South.

St. Louis-born artist Joe Jones (1909 – 1963) went from an unknown house painter to national prominence in the 1930s, becoming well known for his graphic depictions of urban and rural American life. Inherent in his work was a commitment to documenting social injustice and the plight

of the proletariat.

Jones made his vision clear by stating in 1933: “I am not interested in painting pretty pictures to match pink and blue walls. I want to paint things that knock holes in the walls.” And knock holes he did at The Commonwealth College near Mena, a small town on the western border of Arkansas, when he created a mural in the student commons dining hall. The Struggle in the South offered vibrant depictions of sharecroppers struggling to get by, of coal miners under the watch of an overlord, and of a black family in fear and agony of a lynching.

Broken into fragments, the mural began a period of slow decline due to misuse and neglect. Pieces were used as building material to line two closets in a house in Mena. Preservation seemed unlikely, but in 1984 archivists at UA Little Rock salvaged the severely damaged mural fragments and stored them out of sight in the art collection storage area

at the university. There it sat for 28 years under the protection of the art department.

Hope for the mural’s survival flickered to life in 2009 when the Saint Louis Art Museum asked to conserve a portion of the mural for the museum’s exhibition “Joe Jones: Painter of the American Scene.” The exhibition brought new attention and renewed interest to Jones’ body

of work, and the mural itself became a central focus of the exhibition.

The mural’s 2010 revival and subsequent attention gave UA Little Rock the opening it needed to bring the entire mural to life once again. In 2012, thanks to a grant from the Arkansas Natural and Cultural Resources Council, 29 mural pieces were sent to Helen Houp Fine Art Conservation in Dallas. Her team of experts spent four years working to restore the mural to its original form.

This extraordinary work of art will inspire new generations to study, discuss, and create their own legacy of social justice and equality. As you view this mural and its compelling imagery, please reflect on the past and the present to understand our civic responsibility to one another.

The Struggle in the South is now permanently installed in UA Little Rock Downtown, at 333 President Clinton Ave. in the heart of the River Market. Visit today!

Jaune Quick-To-See-Smith

American (St. Ignatius, Montana, 1940 -)

Ode to Chief Seattle (State II), (1991)

19 ¾” x 27”

lithograph

Edition 28/35

Printed by Michael Sims at Lawrence Lithography Workshop

UALR Friends of the Arts Special Acquisition Fund

UA Little Rock PC 1997.002

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (Salish, the Salish and Kootenai Nation, Montana) is an American Indian artist who deals with issues that impact our world in her work. This print uses symbols and patterns to convey a message about human interaction with the environment.

Lithography

Developed in the eighteenth century by a German music publisher, lithography is based on the premise that oils and water do not mix.

An artist draws the image with an oily medium, traditionally on a lithographic stone (a unique, Bavarian limestone). The stone and image are treated chemically so that the image area will attract the oily, rolled-on ink and the non-image area will repel it.

Toulouse-Lautrec famous posters for the Moulin Rouge are beautiful examples of 19th century lithography. Contemporary lithographers sometimes use aluminum plates in lieu of the stones. Lithography is especially well suited to multi-color prints. A lithography press is required for printing.

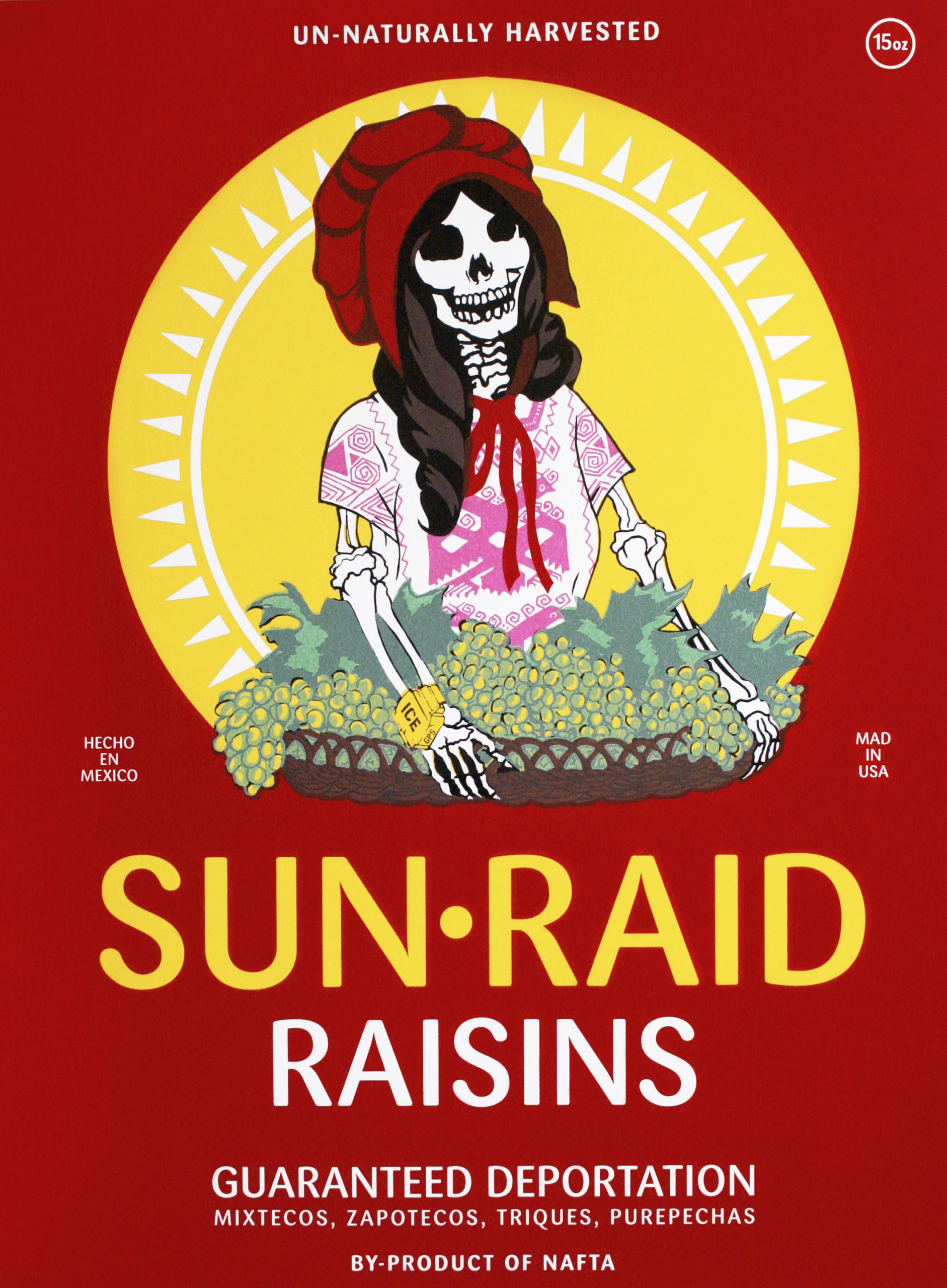

Ester Hernandez

American (Dinuba, California, 1944 -)

Sun Raid (2008)

20” x 15”

screenprint

Edition: 18/50

Printer/Publisher: Coronado Studios, Austin, Texas

UA Little Rock PC 2011.004.232

In Sun Raid, Ester Hernandez transforms a familiar raisin box to make a statement about the situation many farm workers are facing in the United States. The wholesome face normally found on the front of the box is changed into a skeletal farm worker wearing a huipil, a native Mexican dress. She wears a security-monitoring bracelet labeled ICE, for the Immigrations and Customs Agents, signifying looming deportation.

Messages on the box are changed to read “Product of NAFTA,” and “Deportation Guaranteed.” Hernandez uses the names of Mexican indigenous groups from the Oaxaca area because they make up a large number of farm workers in the United States. She hopes her work provokes a dialogue about the issues that effect a population that is often invisible to the mainstream public. Her concern for farm workers can be seen in a similar image she created 27 years ago, titled Sun Mad. She transformed the same raisin box into a statement about the overuse of pesticides and the effect it has on our bodies and environment.

Screenprint / Silkscreen (Serigraphy)

Silkscreen (or serigraphy) is a printing process that uses a woven mesh (traditionally silk) to support a stencil printing technique. Open areas of the mesh act as the stencil, which allows ink to transfer onto various materials (i.e. paper, plastic, fabric and metal). Ink is pressed through the mesh of a silkscreen with a fill blade or squeegee. When the squeegee is moved across the screen stencil, it forces the ink through the openings of the mesh onto paper, plastic, fabric, or metal.

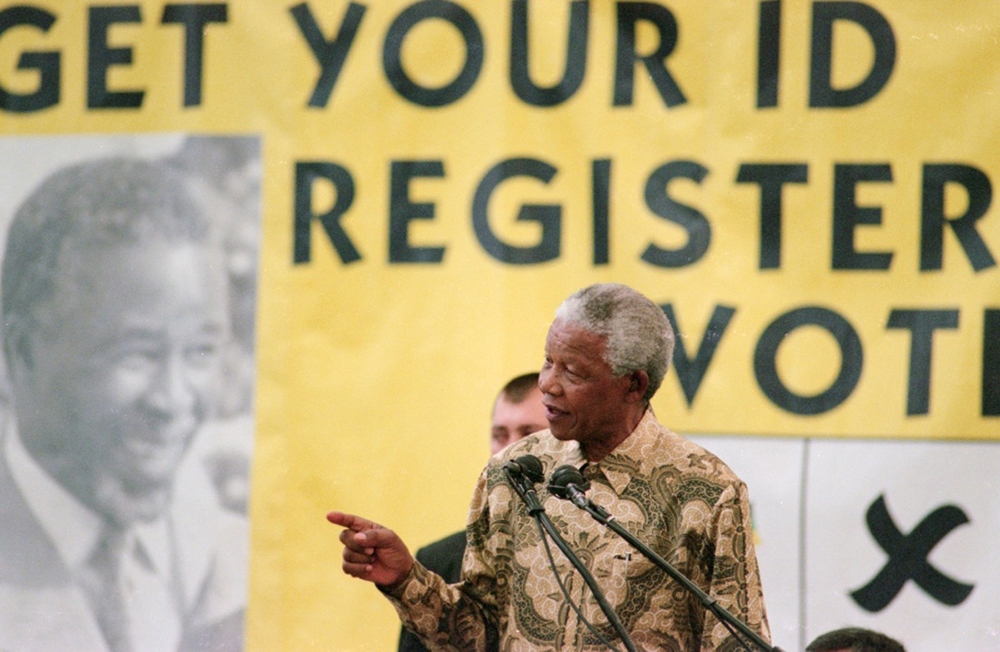

Benny Gool

South Africa

Nelson Madela (Get Your ID Register to Vote), (cir. 1994-98)

40” x 60”

chromogenic

photograph mounted on aluminum with plexi-glass fronts

Gift of Jeff Jaffe, Pop International Galleries, Inc.

UA Little Rock PC 2017.036

Benny Gool is a South African photojournalist who was privileged to chronicle the life of Nelson Mandela in public and private over three decades. It was in the guise of an anti-apartheid and human rights activist that he first picked up a camera to begin documenting the injustices of a divided nation. He went on to capture the inexorable and stirring transition to democracy, the tumultuous truth and reconciliation process, and South Africa’s “homecoming” as a respected member of the global community. The catalyst was one man, Nelson Mandela and through Gool’s camera we are taken on that man’s journey from incarceration to beloved and inspiring world leader.

Marianela de la Hoz

Mexican (Mexico City, Mexico, 1956 -)

Your Reflection Into Mine (2014)

10” x 12”

egg tempera on board

Image Courtesy of the Artist

UA Little Rock PC 2015.012

Marianela de la Hoz encourages viewers to engage and reflect upon the significance underlying the symbolism of mirrors and their functions. Mirroring and thinking are two concepts that are suggestive and interconnected. To think means to reflect, and the mirror serves as the primary object to talk about reflection. Gender lines are blurred in Your Reflection Into Mine, which figure is female and which figure is male?

An image of this painting was reproduced on a billboard in the Hillcrest Neighborhood in San Diego, California at part of the gay pride celebration and awareness.

Elizabeth Brim

American (Columbus, Georgia, 1951-)

Gothic Pillow (2013)

3 5/8″ x 13 1/4″ x 11 3/4″ irr.

etched, fabricated, inflated steel

UA Little Rock PC 2013.019

Elizabeth Brim is a blacksmith known for fabricating feminine imagery in her ironwork, but is a specific material inherently masculine or feminine? Brim is known for her technique of inflating forged steel. In 2012, David Clemons was the resident metals artist in the Department of Art and Design. He invited Elizabeth Brim to campus to demonstrate of her process.

Thom Hall

American (Fayetteville, Arkansas, 1948 -)

Sylvia Moskowitz with Pink Breast (2003)

29 1/2″ x 22 1/2″

watercolor crayon, gesso, gouache on paper

UA Little Rock PC 2006.012

Since 1975, Thom Hall has worked almost exclusively with the human figure. His subjects are friends, self-imagery, and a very complex theatrical character known as Sylvia Moskowitz. Sylvia has the ability to age and become young again and to express an amazing range of character traits.

Thom Hall explains: “Sylvia Moskowitz is me – but with a bit of my mother, and a bit of my grandmothers, a bit of the bejeweled Jew dog turban dames of Miami circa 1958, a snappy dash of Joan (Crawford) and Bette (Davis) and Marilyn (Monroe) and Jane (Mansfield) and Judy (Garland) and Lady Day (Billie Holiday) and Miss Ross.”

Hall is very passionate about color and line, tension, movement and energy, which are really little abstract elements that find themselves coming together in his figurative images. His work is more expressive than literal. Hall adds: “I don’t really care about realistic technique, but feeling and expression of emotion are essential elements. For me, stuff doesn’t matter, but people do. “

“Drag is about many things. It is about clothes and sex. It subverts the dress code that tells us what men and women should look like in our organized society. It creates tension and releases tension, confronts and appeases. It is about role-playing and questions the meaning of both gender and identity. It is about anarchy and defiance. It is about men’s fears of women as much as men’s love of women and it is about gay identity.” Roger Baker, author of Drag: A History of Female Impersonations in the Performing Arts, New York University Press, 1994

J. W. Wiggins’

Native American Collection

About the collection

In the summer of 1974, Dr. J. W. Wiggins stepped through the door of the Five Civilized Tribes Museum in the old Indian Agency building in Muskogee, Oklahoma. This first step into the world of American Indian art gave no indication of the adventures that lay ahead or that the art would become the defining part of whom he is today. In 2004, he donated his collections to the University or Arkansas at Little Rock.

Dr. J. W. Wiggins reflects: “Where do you find this art?” is a question I am frequently asked. My response is that art galleries, Indian markets around the country, and individual artists are all important sources for acquiring the works. However, I stress that it requires diligence and patience to find the art. The collector must be prepared to spend time and energy to locate the artists and their work and should expect today’s artists to be well educated and savvy about their art. I invite you to join me on a journey through my collection, a fascinating introduction to contemporary Indian art from the heartland of the North American continent. My hope is that you will enjoy viewing these artworks as much as I have enjoyed collecting them. If so, you will experience truly a unique journey.”

From that first venture into the world of Native art to the present, Dr. J. W. “Bill” Wiggins has been an avid collector. Today, his collection consists of more than 3000 works of art, including paintings, sculpture, beadwork, baskets, pottery, carvings, and other items. The geographic regions represented range from southern Oklahoma through the northern Plains into Canada and on to the Arctic coast. The emphasis is on the heart of the North American continent with occasional inclusions from tribal artists in other regions.

The art reflects his travels over the years, which initially were defined by an interest in canoeing and wilderness. Yearly trips to Canada, which had begun in 1971, allowed him opportunities to see and acquire Canadian First Nations and Inuit arts. Later, his interest in indigenous arts began to direct his travels.

Initially, his interest in the art was in the art forms and not the cultural statements. However, he quickly learned that to truly enjoy and understand what he was seeing, he had to know as much as possible about the culture. The more he understood the culture, the more he could appreciate the art. Cultural understanding allowed the artworks to come alive and be more meaningful.

Cyril Assiniboine

(Contemporary Canada) (Saulteau) (1959 -)

untitled (Warrior in Red) (1982)

22” x 28”

acrylic on canvas

JWW2008.136

Cyril Assiniboine, a Saulteaux born in 1959 on the Long Plain First Nation community near Portage la Prairie, Manitoba, dramatically captures the essence of the powwow dancer and the elaborate regalia of his culture.

William Wilson

(Canadian Woodlands) (Ojibwa)

Mikinooko Onini (Snapping Turtle Man) (2007)

17” x 14”

art marker on paper

JWW2008.09

The turtle is a sacred figure in Native American symbolism as it represents Mother Earth. The meaning of the Turtle symbol signifies good health and long life. The turtle has great longevity living up to 150 years. According to Native American legends and myths of the Eastern Woodland tribes the turtle played a part in their Creation myth.